March 22 – April 19, 2020

Conflicting Heroes

Conseil des arts de Montréal Touring Program

Guest curator: Michael Patten

Artists : Sonny Assu (Kwakwaka’wakw), Natalie Ball (Modoc – Klamath), Dayna Danger (Métis – Anishinaabe – Saulteaux), Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit – Aleut), David Garneau (Métis), Leonard Getinthecar (Nicholas & Jerrod Galanin, (Tlingit – Aleut)) en collaboration avec Nep Sidhu, Kent Monkman (Cris), Caroline Monnet (Algonquins), Jessie Short (Métis), Skawennati (Kahnawake Mohawk).

Maison de la culture Marie-Uguay

6052, boulevard Monk

Montréal (Québec) H4E 3H6

514 872-2358

Text by Michael Patten

In 2014, I was invited to curate the second edition of the Contemporary Native Art Biennial in Montreal and I chose to explore the theme of storytelling as a lasting and effective method of education for many indigenous cultures. In the stories we tell and in the stories we are told, it is generally the hero who inspires us the most. At times, a hero may allow us to feel compassion for hardships that we may ourselves have never experienced. Or, it is the bravery, the fearlessness and the determination of the hero that compels us to defend what we believe in, stand for what seems fair or just and find the strength to rise up to an oppressing power.

For many communities, notably for indigenous peoples, heroes are necessary. Heroic figures are more than models to look up to, they also unite people. North America was built on the obliteration of our peoples, every effort to salvage our cultures is heroic in nature. It is a way of battling the colonizers while honoring our ancestors. It is a way of dealing with our history. Figures like Louis Riel are a fertile ground for the stories we have to tell today. He is a conflicting heroic figure who defended the rights of the Métis people as well as the French-Canadians of the Canadian Prairies in the late 19th century. In 1869, at Red River, he set up a provisional government to resist the dispossession of Metis land; and in 1885, he led an armed resistance against the Canadian government at Batoche–for which he was hung as a traitor.

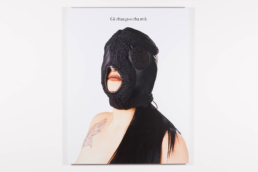

Two Métis artists, David Garneau and Jessie Short reinvest this controversial figure in their work. Garneau portrays Riel in a painting inspired by Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801). The association between Napoleon and Riel underlines the conflicting views of Riel as a historical figure while portraying him as a nationalist symbol. Short’s video Wake Up! shows the artist dressing herself as the famous historical figure. Her transfiguration works to assert Riel as the only Métis icon in mainstream Canadian culture and draws attention to the lack of representation of Metis women in general. Other artists are also making a claim for indigenous women. In Renaissance, Caroline Monnet offers a powerful portrait of indigenous sisterhood. The six women – all of whom are active artists and activists – sit straight and proud in their beautiful attires. Similarly, Dayna Danger’s shows three women in beautifully beaded black masks. They look defiant, powerful, and undefeatable.

Today, the stories that circulate about indigenous peoples are far too often those of drug-abuse, violence, criminal activity and incarceration, which contributed to normalize the image of indigenous peoples as menacing and deviant. This is precisely what Nicholas and Jerrod Galanin condemn with Modicum (2014) showing a riot policed crouched under dozens of disposable coffee cups on which are written the names of non-white people killed by law enforcement officers in the United States. To be a hero for our community is a heavy burden. If you fall, the impact resonates through the whole community.

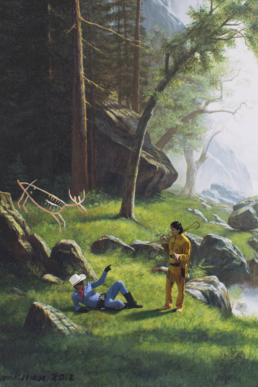

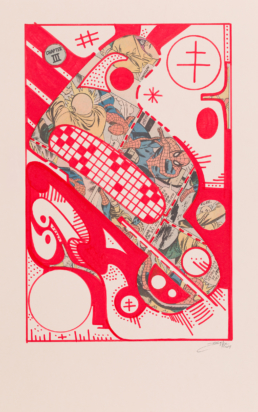

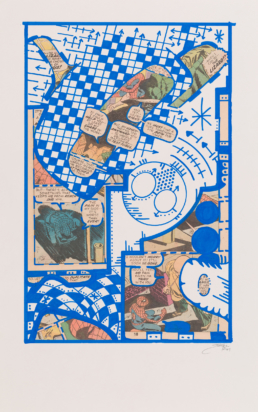

Perhaps that is why many artists are turning to fictional heroes. It offers them the ability to control the narrative. Skawennati has used her characters to imagine new futures in which a different relationship to history can be configured. But fictional characters also contribute to lasting stereotypes. Karl May’s widely famous Winnetou may be seen as a refreshing alternative to the prevailing figure of the criminal ‘indian’ in cowboy stories, but still remains largely problematic. This is a dichotomy explored in Kent Monkman’s diptych. Ultimately, heroes have the capacity to dispel prevalent negative stereotypes to reveal that the potential for greatness that is inherent to any human being. In fact, heroes are just like us.