April 23 – June 21, 2020

Contemporary Native Art Biennial (BACA), 5th edition

Kahwatsiretátie : TeionkwariwaiennaTekariwaiennawahkòntie

Honoring kinship

Curated by David Garneau (Métis), with the assistance of rudi aker (Wolastoqiyik) and Faye Mullen.

Stewart Hall Art Gallery

176, chemin du Bord-du-Lac – Lakeshore

Pointe-Claire, Quebec

The James Bay Project:

Rainer Wittenborn’s and Claus Biegert’s collaboration with the Cree

Arnd Schneider

“We knew: only with the Cree would we be able to create an exhibit about the conflict at James Bay. Very early during our research we came to the conclusion that the Cree have to be first in reviewing our work before we would present it to the public in Canada (starting at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Montreal), the US, Brazil, Europe and Thailand, eleven venues in total.” (1)

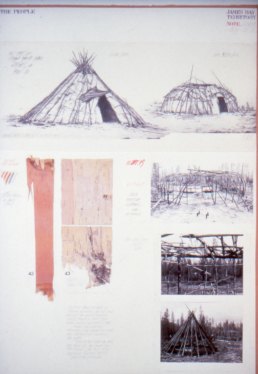

In 1979/80, two Germans, the visual artist Rainer Wittenborn, and Claus Biegert, a long-time member of Survival International, broadcaster and writer on North American Indigenous affairs, visited the Cree First Nation of the James Bay Area / Eeyou Istchee in Northern Québec, whose area was threatened by huge hydroelectric plants, and whose traditional hunting grounds would eventually be destroyed by flooding. The five month project included a detailed survey of the area, many interviews with Elders and knowledge keepers in different Cree villages (for example, in Eastmain, Chisasibi, Wemindji and Mistissini), and also politically embarrassing questioning of the managers of the James Bay Energy Corporation in Montréal. Wittenborn and Biegert had presented their project to the Cree Grand Council in Val d’Or and obtained their active co-operation. Wittenborn and Biegert, both with track records of working on ecological topics and threats to indigenous peoples, had read about the situation in the James Bay Area and wanted this to make the focus of a new work.

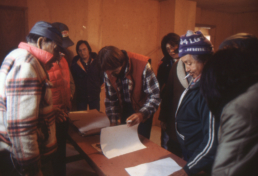

The artists promised the chiefs of the Grand Council that in two years, once their research and art works were completed, they would return and show their work in the new school at Chisasibi, where the Fort George community had been relocated. It was in Chisasibi that the Canadian tour of the exhibition opened. This was a deliberate attempt to expose the often self-serving politics of artists, anthropologists, photographers, and journalists, which a Cree woman, Susan Pashagumskum in Wemindji, had spelled out in very frank terms: ‘They come up here and milk us dry …, and then they never show up again’ (2). The work of the Europeans was accepted and appreciated, not only by the students but also by Elders, whose weekly council meetings Chief Samuel Tapiatic moved to the school building in Chisasibi in order facilitate the widest possible access to the exhibition.

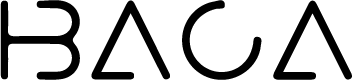

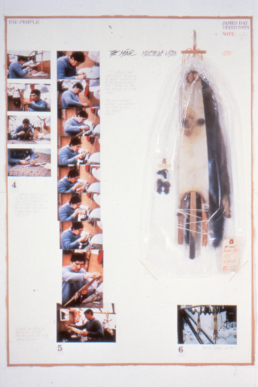

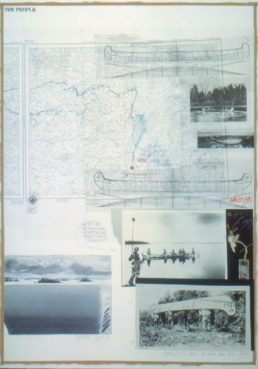

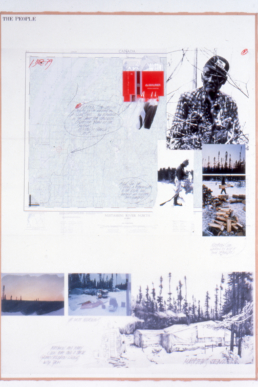

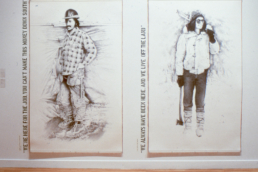

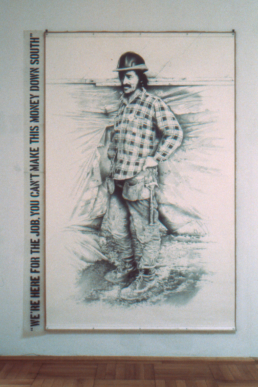

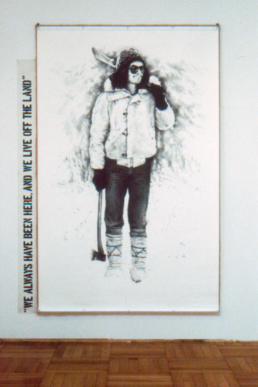

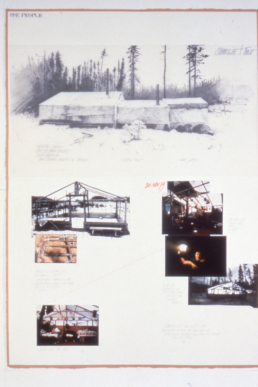

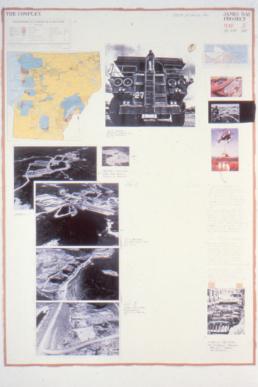

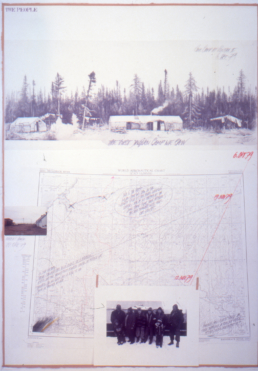

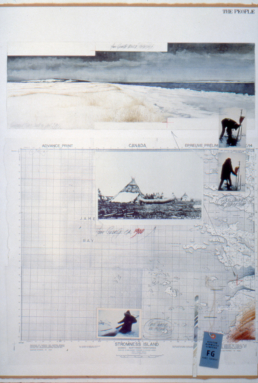

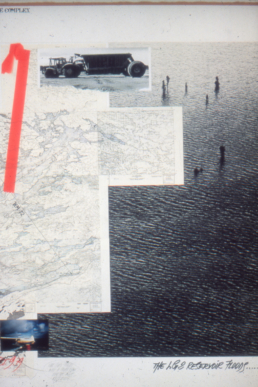

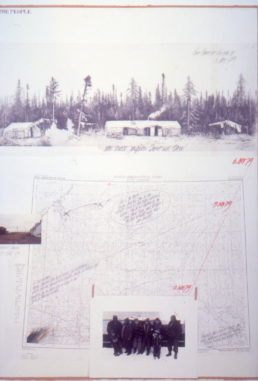

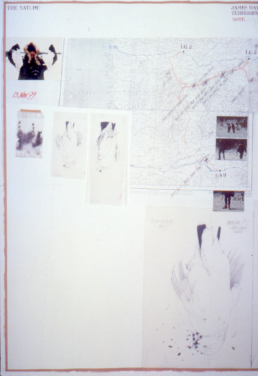

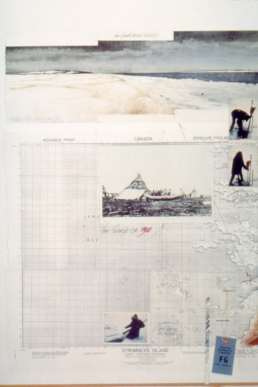

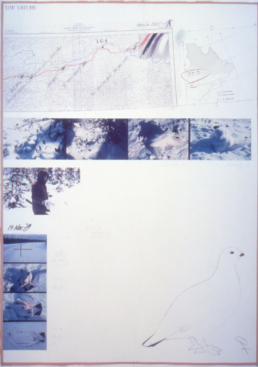

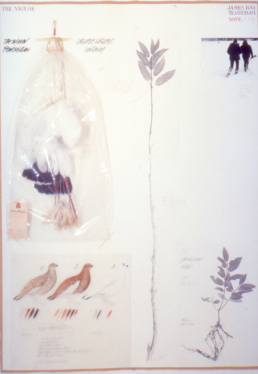

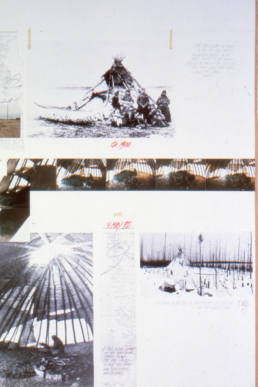

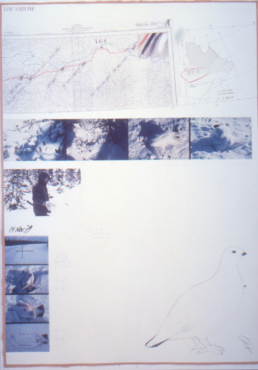

The exhibition had three themes: The Nature, The People, and The Complex. The Nature focused on the environment and basis of Cree livelihoods, now threatened by the hydro-electric plants (figures 30, 31). The People put emphasis primarily on the daily lives and hunting culture in the different villages Wittenborn and Biegert visited. (figures 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 23, 25, 26, 29, 32, 34, 35, 39) It also featured those who had come North to change everything, i.e. the contract building workers (figures 11, 12, 13). Finally, The Complex documented the huge construction works for the hydro-electric plants, dams, workers’ villages and already flooded areas.(figures 24, 27, 28). Since the 1960s the government of Quebec had been making plans for the exploitation for energy use of the vast water resources of Northern Quebec. The James Bay Hydroelectric Project for large hydro-electric plants was implemented from 1971 onward by the James Bay Development Corporation. However, the government did not consult with the Cree First Nation and Inuit peoples of the area, and only after legal opposition by the First Nations and various court rulings, in 1975 signed the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, which paid compensation, and legally enshrined fishing and hunting rights, but also implied the loss of certain lands for the First Nations. Their territories had changed beyond recognition, and eventually an area the size of Belgium had been flooded.

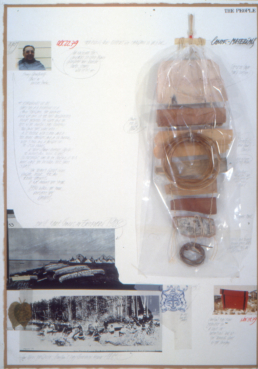

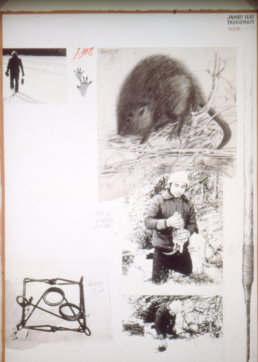

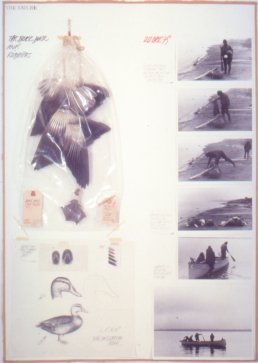

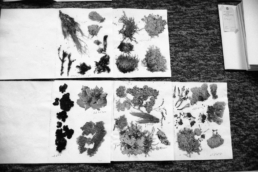

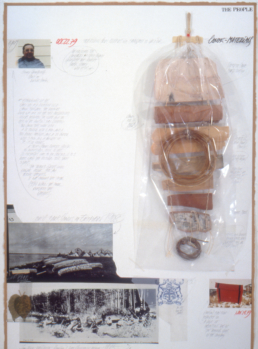

The James Bay Notebook was a principal part of the exhibition, and consists of 60 pages (110 x 75 cm) available in a box and arranged as fold outs, of which we show a selection here from photographic scans. On these pages, broadly chronological and in diary form, large-format collages of text, images, and hand-written annotations bear witness of the journey the artist and the writer took through Cree lands. The exhibition, and especially The James Bay Notebook, incorporated plants collected, traps and other items donated by the Cree, as well as wild fowl (such as Canada Goose and Black Duck), which were put in transparent plastic bags fastened to the pages (figures 14, 15, 37). The James Bay Notebook is crafted in the signature style developed by Wittenborn, already in his series of drawings “Amazon Basin” (1975/1976) where he combined ‘scientific’ information (such as satellite maps) with intricate pencil drawings of the environment and livelihoods of Amerindian peoples threatened by the destruction of the Amazon rainforest. (3)

In the James Bay Notebook, the meticulously executed drawings of environment, animals, hunting equipment, and people, show not only the skills of the highly accomplished draughtsman, but a craft which, beyond virtuosity, gains in expression and sincerity from the time spent in dialogue and learning with the Cree.

A central part of the work is the herbarium, with classifications according to both Western and Cree terminology. On 17th October 1979, Wittenborn showed the plants he had collected so far to Cree Elders in Wemindji, among them the very knowledgeable Elder Geordie Georgekish (figures 2, 3, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22). As suggested by one of the Cree helpers who had provided the contact with the elders, tobacco was later distributed among them as recognition of their classification work.

Wittenborn writes in the travel diary:

“I am laying out the folded pages (with the plants) on the table. We ask for the names and the usage of the plants. With the help of the translator, Claus Biegert notes down for each specimen, its usage as material, food, and medicine. Below the Latin names, the teacher for the Cree language writes down the Indian names with the syllabic characters in Cree. Rarely, there is disagreement, and then the plants go through the hands of all. (…) Geordie Georgekish, maybe already over seventy, seems quieter than the others, has the most comprehensive knowledge, decides as the last, and seems to be the unchallenged authority here. Plants here are something else than just material of study. Already the nomenclature is different, knows no genera, orders, families, sub-families etc. as in our system. The plant stays in direct connection to people and animals, is part of daily life, of daily experience in the bush. There are no problems with the lichen which are difficult to classify. The species Cladonia, for example, Geordie identifies as ‘Wapiscamik – what the caribou eat’. ‘Waekunk’, the black-dotted stone lichen, which we couldn’t identify in Lac Hélène, is known as ‘bread-lichen’; it is ground as flour in hard times and then baked as flatbread.” (4)

Both anthropology and the arts practiced by Westerners have a long history of appropriating from Others who had previously been colonized. However, in terms of artistic excursions into ethnographic terrain, and what later became a growing field of collaboration between contemporary artists and anthropologists (‘the ethnographic turn”) the James Bay Project was far ahead of its time (5). In fact, Wittenborn and Biegert’s artistic research project with First Nation communities provided a substantial challenge to the academic discipline of anthropology, which for too long, and marred by its colonial entanglements, had taken a prerogative on the representation of Others, and only in the mid-1980s began to seriously question its own practices. This was somewhat preceded by the strong political stand of the small radical brand of action anthropology, where anthropologists supported First Nations in legal fights for land and other rights, and which also inspired Wittenborn’s and Biegert’s James Bay Project.

The particular value of The James Bay Project for present and future artistic engagements with First Nation communities lies in its strong political advocacy, and committed ethical stance – present in every aspect of the project, from planning, gaining permission and mutual interest, respectful dealings during the research, and return of results through exhibition and catalogue to the Cree (including, upon the Cree’s invitation a return visit and new exhibition Amazon of the North in 1995) (6). It speaks to the uncondescending, ethically highly conscious attitude of Rainer Wittenborn in this respectful collaboration with the Cree, that when asked in Mistissini by Louise and Kenny Blacksmith if he – an accomplished draughtsman – could also draw plants and animals, he encourages them to make their own drawings and herbarium, rather than providing the couple with his version (‘which could be a very beautiful piece of work, but it would be more my own and not any longer theirs’, as he records in the published travel diary of the project) (7). It is along such lines of respect and ethics of collaboration, where joint artistic research with outsiders can be advanced on First Nations’ terms and own interests.

Acknowledgements

I thank David Garneau for the invitation to write this essay, and Rainer Wittenborn and Claus Biegert for their generous time and help in locating artistic works and materials. All translations from the German are mine. Dedicated to Cree First Nation of the James Bay Area / Eeyou Istchee.

Notes

(1) Wittenborn, Rainer and Biegert, Claus, “Answers to questions by Arnd Schneider and Christopher Wright” (Dialogues), in: Contemporary Art and Anthropology, eds. Arnd Schneider and Christopher Wright, Oxford / New York: Berg, 2006, p.144.

(2) Wittenborn, Rainer and Biegert, Claus. James Bay Project: A River Drowned by Water. Montréal: Museum of Fine Arts, 1981, p. 268.

(3) Wittenborn, Rainer. “The Amazon Basin”, Rainer Wittenborn Landscape Management / Transmitted Pictures, Münster: Westfälischer Kunstverein /Ludwigshafen: Kunstverein, 1977/1978.

(4) Biegert, Claus and Wittenborn, Rainer. Der grosse Fluss ertrinkt im Wasser: James Bay: Reise in einen sterbendenTeil der Erde [The great river drowns in water: James Bay: travel to a dying part of the earth]. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1983. p. 67

(5) Schneider, Arnd, “The Art Diviners”, Anthropology Today, (9), 1993, 2, pp. 3-9, and “Uneasy Relationships: Contemporary Artists and Anthropology”, Journal of Material Culture , (2), 1996, pp. 183-210. Also, Foster, Hal. “The Artist as Ethnographer”, The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Culture. Eds. George Marcus and Fred Myers, Berkeley: University of California Presss, 1995.

(6) Wittenborn, Rainer (in collaboration with Claus Biegert). Amazon of the North. Middletown, Connecticut: Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery Center for the Arts Wesleyan University, 1995.

(7) Biegert, Claus and Wittenborn, Rainer. Der grosse Fluss ertrinkt im Wasser …, p. 140.

Biographies

Claus Biegert

Author, radio journalist, documentary film maker, anti-nuke activist. Several books on indigenous peoples of North America. Initiator of the World Uranium Hearing (1992, Salzburg, Austria) and co-founder of the Nuclear-Free Future Award (1998). Collaborated with artist Rainer Wittenborn (see below) on the highly acclaimed “James Bay Project: A River Drowned by Water” (1982, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts).

Rainer Wittenborn

Artist, professor emeritus, Technical University, Munich. His “James Bay Project: A River Drowned by Water” (with Claus Biegert, 1982, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) was a major artistic investigation and exhibition project, collaborating with the Cree First Nation of Northern Quebec; in 1983 it traveled to the XVII Biennale in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Arnd Schneider is a full professor of social anthropology at the University of Oslo, Norway. He writes on contemporary art, film, and global migrations. Among his main publications: “Appropriation as Practice: Art and Identity in Argentina” (Palgrave, 2006), and as editor, “Alternative Art and Anthropology: Global Encounters” (Bloomsbury 2017), and “Art, Anthropology, and Contested Heritage” (Bloomsbury 2020).